One of the first names mentioned when Gene Pitts suggested a series of interviews with British audio legends was Raymond Cooke, founder and Life President of KEF. In late 1994, I met with Raymond at the KEF factory in Maidstone, in Southeastern England for what was to be a series of conversations about the history of KEF. We started with Raymond’s own introduction to the industry, working for Gilbert Briggs at Wharfedale. Raymond, who had been ill, seemed fitter than when I saw him the year before, he was keen to tell me tales — many of which will never see print — and suggested we meet again. Sadly, Raymond Cooke passed away on the 19th of March, so it turned out to be the last interview he ever gave.

AUDIO: Before you created KEF, you worked with the great Gilbert Briggs of Wharfedale —

RAYMOND COOKE: — and he was great.

A: Was he your mentor at the beginning?

RC: He was my mentor in the commercial sense but not in the technical sense; Briggs was not an engineer and he wasn’t a scientist. We got together to complement each other. He had a very clear ideas about business. That isn’t to say he was the world’s greatest businessman or a tower strength and expertise in the boardroom. But the things that he opined to me during the time that we worked together still come to mind and they’re still true.

For instance, he was not a marketing man. But he once said to me, “The public confused buys nothing.” And of course he was absolutely right. But what was even more extraordinary was how many of the big companies in our industry failed to heed that simple rule. When, for instance, the Japanese went into four different four-channel systems in the 1970s, they all lost. And look at the number of completely false starts that people like Sony have made. You’d think that they’d have brighter people on their boards to prevent that. But he was always very clear. Every proposition and every move made by his company was examined from the point of view of how does it look from outside.

A: What kind of a company was Wharfedale when you worked there?

RC: Very solid. It had a high reputation, but it was quite small. When I joined, the turnover was less than half-a-million pounds a year, total. But the global reputation that he founded was so well done that in its restrictive way it was highly focused at the prime people. He very quickly made friends with C.G. McProud and it was through contacts like McProud that he came to take his books to the States. He eventually arranged the distribution through British Industries Corporation. And that’s how we got started; I eventually joined him in editing the books, as technical editor.

When I joined, he was running the firm himself — head boss, production boss, leaflet writer. He was doing all the things in that firm absolutely right. Anybody who’s got anywhere in the hi-fi business since, be it in Japan or be it in the USA, they’ve always done it his way. I joined to take off his back the technical design. Subsequently I was able to takeover other things, When he reached 65 and was getting rather tired of the whole thing, ultimately I was the one who’d go off and see distributors. I took over the advertising. We were already writing the books; then he gave me the leaflets to do. I had a remarkable, unintended apprenticeship. When I eventually decided to quit the Rank Organisation after its takeover [of Wharfedale] and come and start here, I already had far more experience than I could possibly have had in the ordinary way in another industry.

How I came to leave Wharfedale…I could see high fidelity wasn’t going to get anywhere unless a lot more science was applied. Gilbert Briggs was a bit suspicious of science. Or, shall we say, of scientists. He once wrote of the folly of employing technical people at the head of things because they tend to go after brilliant technical solutions rather than the practical, commercial solution. He had seen many firms go down that way.

It was great working with him because although he wasn’t always right in all directions he was right more than most.

A: So what was Wharfedale’s technological state at the time?

RC: When I joined them, extremely conventional. Gilbert Briggs had designed the drivers himself and they were all paper-coned. Big magnets and so forth. The things worked well, they had high efficiency. Their best system was the three-way, sand-filled corner enclosure. The thing really worked very well. But his claim to fame was that from about 1955 onwards he embarked on a series of lecture-demonstrations all over the world in which the sound of live players was compared with recorded sound.

The first one was in Canada, in a university hall, then St. George’s Hall in Bradford, and then in 1955 or ’56 he hired the Festival Hall. You could hire it for a day for a £140, would you believe, complete with all the stuff.

A: Was Wharfedale one of the most important British makes then?

RC: It was neck-and-neck with Goodmans.

A: Were you starting to want to put your own stamp on a product early on?

RC: Yes. It seemed to me, being a scientist, that when I looked into sound reproduction — which wasn’t my subject; I was originally a chemist and then an electronics man — if only one could bring scientific procedures even to the experimental work, like listening tests, and then to the production work, we ought to be able to produce a better loudspeaker, smaller and cheaper. I think I was the first person to realize that you didn’t have to have a 15in loudspeaker to get down to 20Hz.

I wrote it up for Briggs on one occasion, that we ought to be able to get that response from a 10in loudspeaker provided that the resonant frequency of the 10in driver was sufficiently low. And he wrote back that while what I was saying might be theoretically correct, he wouldn’t have anything to do with it practically because a 10in loudspeaker would very rapidly go out of alignment and get its voice coil rubbing. And I wrote back that that is true if you think of it in terms of today’s suspensions. But if the suspension is redesigned and made in other materials like nylon it will be possible. This correspondence goes back to 1950-51, before Villchur.

A: Your remarks about the need for more science surprise me because certain of your contemporaries, ones who are leery of subjectivists, imply that all of the designing back then was pure science.

RC: No. Very little science.

A: Wild’n’woolly, seat-of-the-pants…

RC: The only people who were into science were Villchur when he came along and Klipsch before that. Most of the other people who were great names in hi-fi in the States, they were just fumblers, they worked on a cut-and-try basis.

A: But the BBC was so influential in the commercial sector, and the dominance of Wireless World…

RC: That was later. Even in the Forties when I started into it, all development work was done subjectively. One cut a hole, had a listen, cut a bigger hole, had another listen and so on. There were very few people around in the trade who understood how it worked.

We got to the point where I took out a number of patents on enclsoure design as it was very clear that I wasn’t going to get anywhere with drive unit design. The firm couldn’t afford the cost of the tooling and every new design needed a diaphragm mold and die casting plus the magnet. I then finally came up against it in 1959 [after Rank acquired Wharfedale] . It was staring me in the face that we needed to do something about diaphragms.

Rank were trying to get into the record business and they also had some not well-defined ambitions in radios and TV. They could see a future in domestic entertainment. The notion was that if they could buy a wholesaler they’d have the whole thing down pat. Complete vertical integration. So they bought a wholesaler. Wharfdale had been a very successful, long established firm run by its founders but the whole thing was beginning to crumble.

In 1960, I thought, “I don’t know what I’m going to do here.” I was director of Wharfedale but one never got to talk to the people in London. I wasn’t being introduced to Rank and couldn’t speak to the new bosses. It became clear that Briggs wasn’t anxious to leave; on the other hand, he had got to 70 so he wasn’t scintillating or looking to the future. He was just trying to keep his little company together for the benefit of the people who worked the for a long time. There was no point in me talking about new ideas.

A: Was it hard creating a hi-fi company in 1961?

RC: Because my relationships in the industry were so good, I had no problems starting up. At a meeting in Paris, at the Festival du Son, John Gilbert of The Gramophone said, “I’ll go on record for the British press if you decide to start on your own. Call a meeting to explain your product and we’ll all be quite happy to take tea.” And I did just that the following November and everybody came. In droves. Percy Wilson [Technical Editor of The Gramophone] said,”We’ll support you — glad to see a new face.” They were getting a bit tired of some of the older faces when they didn’t seem to be doing anything.

We formed the company legally in September, 1961. We finally managed to get assembly started about the end of October and managed to put together at least two of everything we intended to offer. A three-way system in a thin box, the same again in a four cubic foot cabinet which had much better bass, a line source speaker and another was a very thin, flat speaker to go against the wall. We organized the meeting for the whole day. In the morning we set up and in the afternoon everybody arrived, the press, wholesalers, that sort of thing. Ralph West actually took over the demonstration and we went on through the evening. By the end of that day I knew we had no market in the UK at all. One by one, the wholesalers said, “We need another loudspeaker line like a hole in the head.”

A: Too many brands even in the early Sixties?

RC: Too much product, too few sales. And so in the end I got on my bike and literally went off to Europe. And after a week in Europe I came back and I knew I’d got a business.

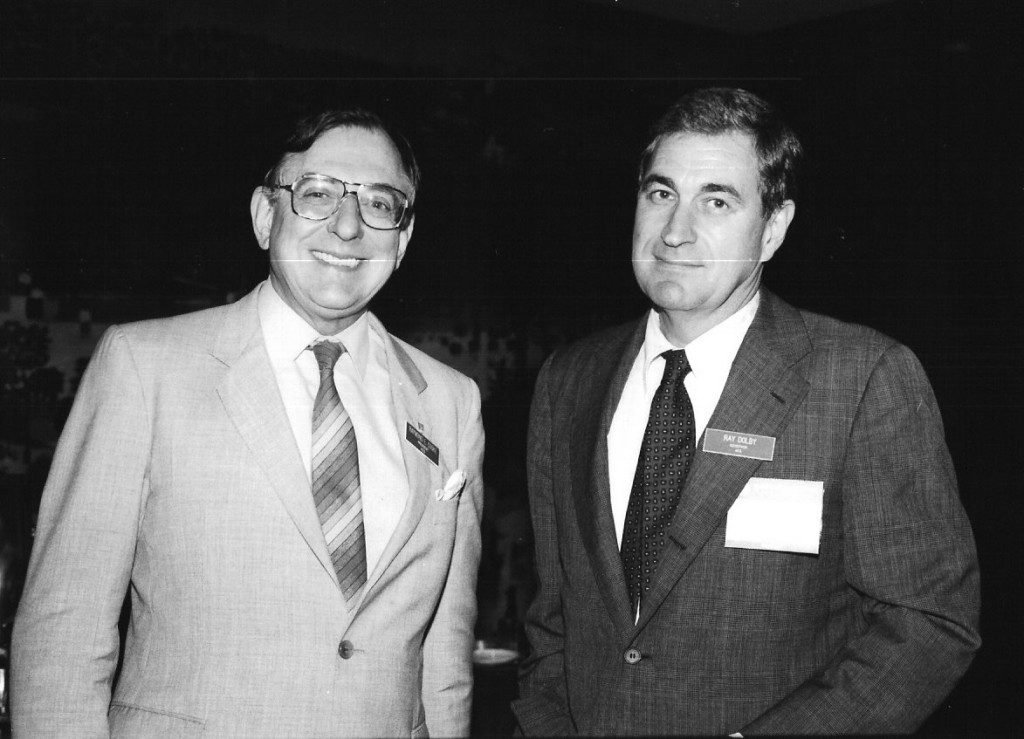

Top photo, Raymond Cooke with Ray Dolby; bottom photo, Raymond Cooke’s personal ID badge at KEF

(Audio, 1995)